Zombie Archetype: The Complete History of the Undead

ALGORITHM HUNTER | PROTOCOL 06 | GENESIS

What is the Zombie Archetype?

The zombie archetype is a foundational cultural construct representing a body without a soul or agency. Historically rooted in Kongo cosmology and Haitian trauma, it has synthesized into a modern global metaphor for viral contagion, societal collapse, and the existential truth of human negation within a hollow, consuming framework.

Key Takeaways

- Spiritual Roots: Originates from the Bantu concept of Nzambi, signifying a supreme spirit or deity of creation.

- Colonial Trauma: Transformed in Haiti into a symbol of eternal, soulless plantation labor and metaphysical theft.

- Romero Schism: Reinvigorated in 1968 as a cannibalistic mirror of social decay and mindless consumerism.

- Scientific Shift: Modern iterations utilize virology and mycology to ground the archetype in a terrifying biological reality.

The Zombie Archetype is the foundational synthesis of spiritual history and physical negation, representing the core truth of the soul-less body as it evolved from the sacred Kongo spirits into a holistic overview of human trauma. In this investigation, we will map the complete history of the undead, providing a definitive synthesis of its evolution from a theological anomaly to the medicalized contagion that serves as the core metaphor for our modern civilizational collapse. The story of the zombie is not a simple chronicle of horror; it is a profound history of the human shadow. It begins with the foundation of the Nzambi in the Kongo basin, where the spirit was not a monster but a sovereign force of the sky. We must look at the truth of how the Trans-Atlantic slave trade acted as a necrotic vector, twisting this divine foundation into the zonbi of the Haitian plantation—a body trapped in eternal labor, denied the release of death.

This overview requires us to witness the synthesis of African cosmology with the crushing reality of colonial violence, creating a figure that represented the ultimate theft of the self. As we trace this history into the 20th century, we see the holistic transformation of the archetype. The Imperial gaze of the 1930s packaged this trauma for Western consumption, but it was George Romero who provided the core schism in 1968, democratizing death and shifting the truth of the zombie from a magical slave to a universal, flesh-eating mirror of ourselves. Today, the synthesis is complete as we merge this spiritual history with the science of mycology and virology. We are no longer looking at ghosts; we are looking at the foundational reality of our own negation. This is the truth of the hollow man, the consumer mind-virus, and the existential overview of a world that has forgotten how to die.

The Sacred Roots: Nzambi a Mpungu and the Kongo Basin

The birth of the zombie archetype is not found in the sterile labs of a screenplay but in the high heat of the Kongo Basin where the soul was never considered a singular or static thing. To find the foundation of this nightmare, we have to look past the rotting skin of cinema and toward the intricate spiritual architecture of the Bakongo people. Their history tells of a universe divided by the Kalunga line, a watery veil that keeps the living separate from the spirits. At the apex of this holistic system sat Nzambi a Mpungu, the supreme architect of all motion and the source of the divine spark. In this pre-colonial reality, death was a transition and a movement toward the ancestral land of Mpemba. The concept of the soul was split into components where the life force was shared by all but the individual agency remained a fragile gift.

When the Trans-Atlantic trade ripped these people from their ground truth and scattered them across the Caribbean, the spirit of Nzambi was forced to undergo a violent synthesis. On the plantations of Saint-Domingue, the divine became the desperate. The linguistic drift began to turn the word for god or spirit into a word for the prisoner. The term Nvumbi, which once described a visible ghost or a body without a soul, began to merge with the Kimbundu word Nzumbe until it solidified into the Haitian Zonbi. This was the core trauma of the middle passage where the fear was no longer about the end of life but about the negation of death itself. The enslaved people watched their brothers work until they collapsed, and in that agony, they hallucinated a fate where the master could reach into the grave and pull the soul back for an eternity of labor.

The Haitian Crucible: Metaphysical Theft and the Ti Bon Ange

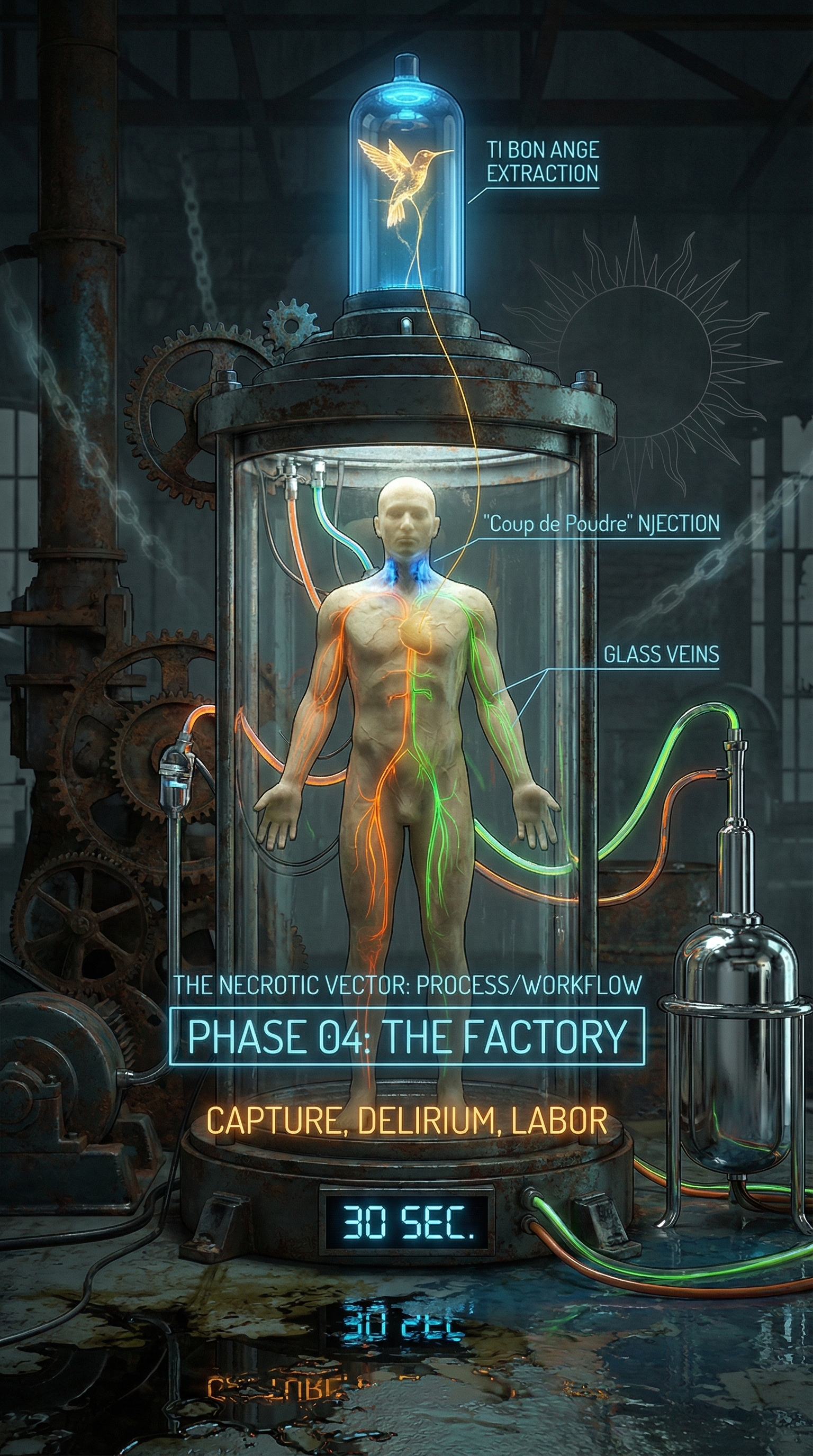

The history of the zombie archetype is a record of a metaphysical heist where the divine was ground into the sugar-choked mud of Saint-Domingue. The foundation of this horror was never about a body rising from the dirt to eat brains, but about a soul being stolen so it could never leave the field. In the theology of Haitian Vodou, the human soul is split into two distinct parts: the gros bon ange, the breath of life shared by all things, and the ti bon ange, the little good angel that houses the individual’s memory, personality, and will. To create a zombie, a bokor does not need to reanimate a corpse; they simply need to capture the ti bon ange in a jar, effectively lobotomizing the victim’s spiritual presence and leaving the physical shell as a pliable, mindless drone.

The horror here isn’t the death of the body but the theft of the grave itself, as the zombie became the only creature on earth denied the release of the afterlife. This was a socio-political mechanism used to enforce the order of secret societies and a reflection of the trauma of a people reduced to livestock. The zombie archetype is the ultimate legacy of the corvée system and the crushing weight of eternal labor where the slave’s greatest fear was not dying, but being forced to work forever in the cane fields even after the heart stopped beating. Every time a bokor administered the coup de poudre, they were performing a ritualized reenactment of the Middle Passage, stripping away the history of the man to create the tool of the master.

The American Export: William Seabrook and the Colonial Gaze

The American influence on the zombie archetype represents a violent synthesis where theology was murdered to feed a burgeoning industrial appetite for the macabre. This was not a passive observation of a foreign culture but a holistic extraction of trauma during the US Occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934. The American military brought a colonial gaze that viewed the Haitian spirit as something to be categorized and sensationalized. William Seabrook served as the primary vector for this cultural contagion through the publication of his 1929 sensationalist travelogue, The Magic Island. Seabrook did not seek the theological depth of the Kongo sky gods; he hunted for the leaden work crew and the unseeing eyes that confirmed his own prejudices.

By packaging the zonbi as a soulless human corpse endowed with a mechanical semblance of life, Seabrook created the export version of the monster. He stripped the zombie of its tragic, protective roots and presented it as a singular object of horror, allowing the American public to consume Haitian pain as entertainment. This visual manifestation reached its zenith with films like White Zombie (1932), which solidified the “Zombie Master” trope and projected Western anxieties about labor, race, and the loss of autonomy onto the screen.

The Romero Schism: Consumerism and the Universal Ghoul

In 1968, George A. Romero orchestrated the most significant mutation in the history of the zombie archetype with Night of the Living Dead. While he initially called them “ghouls,” the public grafted the term “zombie” onto these flesh-eating revenants. Romero democratized the monster; it was no longer a victim of a specific sorcerer but a universal plague that could infect anyone regardless of race or class. This shift moved the archetype from the realm of the magical slave to the realm of the cannibalistic mirror.

In Dawn of the Dead (1978), the mall setting transformed the zombie into a biting satire of late-stage capitalism and mindless consumerism. The undead wandered the aisles out of motor memory, reflecting a society that had lost its ti bon ange to the hunger of the market. This transition laid the groundwork for the modern medicalized zombie, where the cause of the outbreak shifted from vague radiation to the sterile terror of virology and mycology, as seen in the Resident Evil franchise and The Last of Us. We are no longer looking at ghosts; we are looking at the biological truth of a species that has become a parasite upon its own future.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the origins of the Zombie Archetype?

The archetype originates from the Kongo Basin’s spiritual concept of Nzambi, a creator spirit, which was transformed into the “living dead” during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

How did Haitian slavery affect zombie lore?

Slavery turned the zombie into a symbol of eternal labor, where the fear was not death, but being denied the afterlife to work forever on a plantation.

Who is Nzambi a Mpungu?

Nzambi a Mpungu is the supreme creator deity in Kongo cosmology, representing the architect of the universe and the source of all life and motion.

What role did William Seabrook play?

Seabrook authored The Magic Island (1929), which introduced the Haitian zombie to Western audiences, sensationalizing the concept and stripping away its original theological complexity.

Why is George Romero significant to the archetype?

Romero redefined the zombie as a flesh-eating, contagious, and universal threat, shifting the metaphor from individual slavery to societal collapse and mindless consumerism.

Conclusion

The Zombie Archetype remains our most potent modern myth because it refuses to lie about our own condition. It is the history of the soul being stripped away by the machine, whether that machine is a sugar mill or a shopping mall. From the high heights of the Nzambi to the fungal blooming of the cordyceps, the zombie tracks the evolution of our own negation. We have become a culture of the hollow man, and until we address the foundational trauma that birthed the living dead, we will continue to see our own reflection in the unseeing eyes of the horde.

Sources & Further Reading

- Visualizing the Abyss: The Necrotic Siren — Midjourney prompts for the visionary horror aesthetic of the undead archetype.

- The Rotting Landscape: Environment Prompts — Visual design prompts for post-apocalyptic environments and the fungi-reclaimed world.

- The Infected Host: Character Design Prompts — Biological horror character design for the medicalized zombie and viral mutations.

- The Corporate Vector: BSL-4 Lab Tech Visuals — Visual prompts for the corporate and scientific origins of modern zombie plague.

- The Fungal Bloom: Nature Reclamation Visuals — Mycological aesthetics and the final evolution of the zombie archetype.

- The Shadow Historiographer: System Prompt — Deep-dive methodology for creating the narrative architecture of the Necrotic Vector.